Dal “Padrino” a “Mamma Lucia” – Storie Italiane

Questa storia è scritta dall’Australia: luogo lontano dall’Italia. Eppure per me questi due luoghi saranno sempre connessi, perché sono nato in uno e cresciuto e dimoro nell’altro. Ci vuole per ne fare senso: questa vita vissuto attraverso mezzo del mondo. In qualche modo le scatole facile che la società crea: questo paese qui , quel paese lì; non trovano pace nel mio cuore. Come posso ripartire il mio ventricolo sinistro in una terra e la destra in un’altra? C’è un problema con questo modo di pensare, che spezza questo mondo in paesi separate; perché dentro il mio singolo corpo umano tengo storie da due.

Here is a strange kind of foreignness. A foreignness that insists we must be strangers to ourselves. It is a foreignness stitched from unknowing and forgetfulness. My own and those around me. So easy to substitute a neat package, that tells us all we need to know about human lives of millions. So “Italian” “American” “Australian”, or any such label, is prone to mislead – as we repeat again and again the two or three simple tales that we have chosen to put in our neat package that tells us all we need to know – everything hidden under the label. It is in such a place we begin – and where are we going? Well until we reach the end who can say? But we are seeking forgotten stories, or stories we have never known, and in their telling seeking understanding.

So let us begin our journey with what we believe we know.

What images rush in to fill our mind when we hear the words “Italian” or “southern Italian”? And how have those images been built in our minds by our own choices; and the choices of those around us? For people of Italian background in English speaking diasporas it is a pattern captured by the words of Fred Gardaphé:

Italian Americans are invisible people. Not because people refuse to see them, but because, for the most part, they refuse to be seen. Italian Americans become invisible the moment they could pass themselves off as white. And since then they have gone to great extremes to avoid being identified as anything but white, …

By becoming white, they have paid a price, and that price is the extinction of their culture. It is that near extinction of Italian American culture that has enabled them to remain invisible.[1]

It is an easy enough course. With time – anglicised names – and the right accent – very easy. And truth be told it is rather comfortable and even sometimes necessary for difference to be forgotten. And the people of southern Italy have understood necessity. Gardarphé’s words don’t translate exactly to an Australian context. We don’t have hyphenated Australians in the same way that America does, nor do we so much speak of whiteness — yet there is a constant discussion that seeks to define “real Australianness” and who belongs and what is required of us to belong.

Counterintuitively, the fictional world created by Mario Puzo – a well-known American author of southern Italian heritage – helps us unpick the threads. Puzo has been immensely influential in shaping how people of Italian heritage are perceived in the English speaking world, although his words discussed below suggest that he himself regrets that influence.

Puzo’s family hailed from Pietradefusa (a name surely meaningless). It is a village in the hills of Avellino; a short trip north-east of Naples.

The Godfather

Puzo wrote The Godfather, a book which gave birth to one of the most successful English language movies in history. Many love the movie. Yet it has always grated. It was always palpably mendacious in its portrayals. Of the Godfather, Mario Puzo was later to write that he wrote it because he had to. In his own words “he sold out” to make money as an indebted artist with a family to support. The unavoidable compromises which are the lot of the poor. The work itself; a glittering bauble: underneath disconnected from much more profound stories, but the kind of thing that sells. Of course, for all that, The Godfather is a great work of art and appeals to such a wide audience not only because of its strength as a work of fiction and the artistry of its actors in its movie version – but also because it is about the loner and powerful anti-hero – who struggles against an unjust reality and wins (although it costs him dearly). In this respect the tale is not specifically about anyone: southern Italy and America are just a particular stage for retelling of the same universal legend that all humanity shares. The same basic story is told innumerable times in our collective myth making.

Nonetheless, the movie, although produced by Italian Americans themselves, casually traffics with received prejudices about Italy and Italians. The movie sold in part because it fed (and fed off) the need of American society to confirm dark thoughts about the Italian “other” in its midst. Although the Godfather series includes brief (and well acted) flashbacks to Sicily, its treatment of the “old country” is superficial – as its depictions of Italian Americans are cartoon cutouts.

In Godfather II a corrupt politician, Senator Geary, is used as the mouth-piece of such shallow attitudes. He expresses the worst of the bigotry that from time to time new Italian arrivals had experienced in America, revealing his contempt for Italian-Americans in a private meeting with Michael Corleone. Always corrupt, and corruptible, Geary is brought to heel by Corleone. With more than a little irony, the Senator becomes the spokesperson of the deepest suspicions about these “foreigners” in the American polity and the rejection of those suspicions. He has been both intimidated and bought off to speak in favour of the Mafia boss:

These hearings on the Mafia are in no way what-so-ever a slur upon the great Italian people. Because I can state from my own knowledge and experience – that Italian-Americans are among the most loyal – most law-abiding – patriotic, hard working American citizens in this land. And it would be a shame, Mr. Chairman, if we allowed a few rotten apples to bring a bad name to the whole barrel. Because from the time of the great Christopher Columbus up through the time of Enrico Fermi right up to the present day – Italian-Americans have been pioneers in building and defending our great nation. They are the salt of the earth and one of the backbones of this country.

Geary himself believes none of this and the viewer is implicitly invited to share his opinion. His words come nowhere near anything that is real – either in a positive or negative sense. Merely false dichotomies that fail to capture the spectrum of human life which is found in the stories of any people.

The background for such attitudes are found in the currents in broader American society as it responded to the arrival of such incomprehensible and frighteningly different people on its shores. The heyday of Italian migration to America was an era when white supremacists sought to separate black and white and undo the outcomes of the American Civil War. Italians were of dubious “racial stock” in this world.

Soon enough, America closed her doors to these arrivals as its most brutal thinkers turned their thoughts to stemming the genetic tide washing in. Italians and other arrivals from southern and eastern Europe dehumanised as mere human pollution, fouling the pure and purely mythical whiteness of America’s “better” stock. Even Italian race theorists aided and abetted their enterprise. Cesare Lombroso, a northern Italian himself turned his “race science” towards “proving” that southern Italians were inherently inferior. His toxic theories played a part in America closing its doors in 1924 – for they were one of the justifications for the closure.

Such things are now faded in the past – in a collective act of (almost) entire forgetting. It is of course a blessing for America and its new people. But the forgetfulness has a price. For both new arrivals and the society in which they arrived agreed to forget that they were different. For the new arrivals – a hefty price was to be paid. It was forgetting who they had been. For American society it obscures the nature of the multiple racial divisions and prejudice that still beset America.

Puzo – ironically enough – himself provides us a pathway out of this cul-de-sac. He draws our attention to the sleight of hand – like the master magician who shows us how the magic trick was done. We must look to his other works, such as The Sicilian and The Fortunate Pilgrim to see the trick.

Like the Godfather – they also made it to the screen in one form or another – although of course most of us are only aware of the Godfather – and then not through the written text – but only through its film version.

The Sicilian

The Sicilian speaks to us of what is lost in the shorthand sketches that pass for knowledge of southern Italy. Stories left untold. In this case the story is consciously about an Italian reality and tells a story that we don’t usually hear. Here again we find a mafia boss, but he is on the margins and his role hints at a deeper story as he appears as man-at-arms for an ancient baronial aristocracy. Rather “the Sicilian” tells the story of Salvatore Giuliani: a bandit-come-sicilian-nationalist-leader, who in post war Sicily traced a trajectory reminiscent of Robin Hood of English legend. (Here again we find the universal anti-hero). Yet the movie – from its portrayal of the sights and sounds of farm workers harvesting wheat with nothing more than handheld scythes – to the conversations of townsfolk, priests, gentry, intellectuals and politicians – introduces us to a many layered world – and a different reality. Even as we view it – we are conscious we are only seeing the surface. So much that is unknown of this ancient world is left untold. Its strangeness is its undoing, for with few familiar and comforting cues it fails to attract an english speaking world. Too different. Not of interest. Not about “us” (that arbitrary division of human beings into kin and “other”). Not like the stories that are important – stories that are told and retold again and again that every english speaker knows — while other narratives are quietly consigned to forgetfulness. As if the only things of importance to human beings are an impoverished handful of tales from which we can build a cartoon caricature of ourselves. As if we cannot bear to hear the thundering diversity of human voices that no single culture could ever contain.

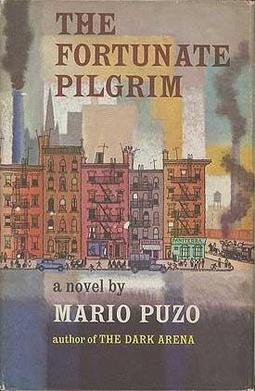

The Fortunate Pilgrim

Puzo’s the Fortunate Pilgrim is almost entirely unknown. Yet it is his most illuminating work. Puzo described it as his greatest work: encouraging us to explore it. Although it was written before the Godfather was conceived – here we find the invisible puppet threads that the Godfather hides. The irony abounds; for in an interview, Puzo reveals that the archetype – the person who inspired the character of the Godfather – was no man at all. It was in fact a woman: Puzo’s own mother. She was a first generation Italian who migrated across the seas to America. Her toughness (which in the Godfather is represented in Vito and Michael Corleone) was born of raising her children alone when her husband lost his sanity. Her life is fictionalised in the Fortunate Pilgrim in the life of its principal character: Lucia Santa.

Whenever the Godfather opened his mouth, in my own mind I heard the voice of my mother. I heard her wisdom, her ruthlessness, and her unconquerable love for her family and for life itself. … The Don’s courage and loyalty came from her; his humanity came from her… and so, I know now, without Lucia Santa, I could not have written The Godfather.[2]

It is an irony redoubled by the virtual invisibility of the lives and voices of the Italian women in the Godfather.

The Fortunate Pilgrim takes us to a world that has now disappeared. It is the squalid and desperate world of first and second generation Italian migrants in the bowels of early 20th century New York city. This world is hinted at but glossed over in the “manly” adventure of the Godfather. There it appears only as a backdrop to shallow myths of masculinity.

The Fortunate Pilgrim has no time or sentimentality for such playthings. It does not allow us to look away from the bitter but rich lives of a desperately poor family which represents the reality of that experience. We see its lived meaning through the eyes of those who lived it. It is clear that Puzo is documenting this world – in such a way that its strange and different characteristics would not be forgotten as cultural and generational change rapidly swept it away. In such a way that the “other” disappears and we sit as silent observers at the kitchen table of the human lives that were traced out in this time and place in America.

Santa Lucia is the indomitable hero of this story – but around her are gathered children and neighbours. Carefully woven into its narrative, like archival notes, are realities that speak of their truth.

As we are introduced to Lucia we find her gathered with other women who had come like her from Italy – lamenting the behaviour of the young.

The women talked of their children as they would of strangers. It was a favourite topic, the corruption of the innocent by the new land.

Here we see see the reality of the vast chasm that opens between those who crossed the sea and their children who grew up in a new land. Yet these women as Puzo drily observes, were hardly in any position to lament the old ways for:

They spoke with guilty loyalty of customs they had themselves trampled into dust.

For in truth they loved their new land but there was a price.

Audacity had liberated them. They were pioneers, though they never walked an American plain and never felt real soil beneath their feet. They moved in a sadder wilderness, where the language was strange, where their children became members of a different race. It was a price that must be paid.

America, America, what different bones and flesh and blood grow in your name? My children do not understand me when I speak, and I do not understand them when they weep.

We see this price woven through the tale again and again in small family conflicts and in moments where the chasm opens between old and new. When Lucia’s daughter Octavia, falls seriously ill and must spend months in hospital, Lucia sends her to a private hospital further uptown – using family savings because she was determined that her:

daughter would be treated like a human being, that is, as a solvent member of society.

Yet when Octavia returns she is a virtual stranger.

… They saw an American girl, full blown. Octavia no longer even had her usually sallow skin. Her cheeks were rosy red, her hair waved in a permanent, American style. She was wearing a skirt and sweater with a belted jacket over it. But most of all, what made them feel like strangers was her voice, her speech, and her manner of greeting them. …Everyone stared. What had happened to her? The only ones delighted with this new personality were the two small children,…

Poverty, like an unwelcome stowaway, stalks these families across the seas and it remains an ever-present reality – a lens through which they see the world.

Only the poor can understand the shame of poverty, … the poor are truly vanquished: by their world, by their padrones, by fortune and by time. …To the poor who have been poor for centuries, the nobility of honest toil is a legend. Their virtues lead them to humiliation and shame.

It was poverty that drove Lucia Santa to accept an unknown husband on the other side of the ocean. Poverty ensures her children are virtual wage slaves in the endless struggle for survival facing the family.

In the society from which they come anyone who climbs out of poverty knows it – and they jealously guard their new status (lest anyone pull them back into the common morass). Dr Barbato is one such. His father – poor like the other Italians who had arrived here – enriched on tenements leased to those that came across the seas with him, had educated his son and Dr Barbato considers himself a race apart. When he is called to Lucia’s apartment he is immaculately dressed. He frequents the opera. He lives in a different world than that inhabited by his poor patients. He resents having to under-charge the family because of its evident poverty. He is later outraged that the family send their daughter to the better hospital.

So Bellevue Hospital was too good for these poor ignorant guinea bastards? They wanted the best of medical care, did they? Who the hell did they think they were, these miserabili, these beggars without a pot to piss in,…

When he examines the women of the poor – Dr Barbato sees not women – he sees the poverty that he himself has escaped and must reject.

In his mind they were unclean, unclean with poverty.

With poverty came its twin: unimaginable suffering. Lucia loses her first husband in an industrial accident. Later, her second husband loses his mind. He dies in a hospital for the poor. Later still, her child precedes her to the grave, but she is considered lucky.

Many women had suffered as much or more. Husbands had been killed on the job, infants born misshapen, children had died from harmless colds, small injuries. There was not a woman in the circle who had not buried at least one child … No, no. Lucia Santa had been fortunate to escape for so long a period of time that measure of sorrow due her station in life.

It is an observation that even cursory exploration of genealogical records confirms. For these people, death called often and early.

But the human spirit has a way of transcending even the most difficult of circumstances. And so it is in the story Puzo weaves. Children play and rejoice. Lovers join lives together. Families still find richness in each other and a community life flourishes in this far-away place. Villages are reborn in the human interactions of neighbours in the streets of New York. They cling to a model handed from generation to generation – the ancient wisdom of a people who have weathered many storms – until the young recognise the necessities of change and leave the old ways behind – as they must.

The old ways placed “father” – symbolically at centre of family life – to be obeyed (at least in theory) without question. But in this story it is the matriarch who is at the heart of family life.

Lucia … [a] beleaguered general, pondered the fate and travails of her family, planned tactics, mulled strategy, counted resources, measured the loyalties of her allies.

Government is a faraway and unfriendly force.

She had been born in a land where the people and the state were implacable enemies … For centuries its government had been the most bitter enemy of their fathers and fathers’ fathers before them.

Religious institutions and customs were found in every hamlet and town of southern Italy, but the relationship is complex. Custom was more important than religion for most. The priest, a tolerated interloper – officiated over tribal customs more ancient than the Christian God in whose name the rites were performed.

… marriages, funerals, christenings, death watches, Communions and Confirmations; those sacred tribal customs sneered at by young Americans.

All her children except Sal and Lena had already made their Communion and Confirmation in the Catholic Church, but she had done this as she dressed them in new clothes on Easter Sunday, as part of a primitive social rite. She herself had long ceased to think of God except to automatically curse his name for some misfortune. There was no question; when she died she would prudently take the last rites of her church. But now she did not go to Mass even for Christmas or Easter.

Among those customs was the Sunday lunch – a rite even the young honoured.

… the Sunday feast, which everyone in the family, married or not, must attend—though no command was ever heeded more willingly.

Here we find some of the universals of the southern Italian experience. They are instantly recognisable to anyone who is connected with its culture and in Puzo’s Fortunate Pilgrim we find them meticulously recorded.

Italian Stories: Returning to Italy

We return to the Godfather, to savour a particular scene from Godfather II. It furthers insight into the experience of these new arrivals in America. For a few minutes the filmmakers allow themselves the liberty of focussing on the migrant experience – in a beautiful and poignant scene – before the movie returns to more sellable fare.

A ship sails in past the Statue of Liberty. A beacon of freedom in the distance. In the foreground, the young Vito Andolini (Corleone) is onboard. The solemn faces of his fellow travellers stare out at this new world. There is no moment of rejoicing. Just the faces of people who have endured and who know too well how easily dreams are stolen away. It is a moment of suspended judgement. Nino Rota’s The Immigrant Theme, scores this part of the movie. In full, the work is longer than the section used in the movie. It beguiles us with an initial lightness: celebration at a voyage ended and the hint of new possibilities. Quickly this theme is crowded out and does not return. It gives way to a magisterial movement of inexpressible grief and irreparable loss. Here on the shores of the new world, the music looks back to the old and makes us mourners for all that has been lost. It memorialises the price paid by mothers and fathers that arrived here and alludes to the deeper stories of suffering that drove one of the largest migrations in human history. Only at the end does the music turn again to America. A brief ray of hope appears and we turn to the future.

The next time we see the Statue of Liberty she is framed in the bars of the window of the Vito’s quarantine cell. He has been processed, together with the other arrivals, like so many cattle, through the stalls, indignities, probings and proddings of medical and immigration officials of Ellis Island. They have arrived in America and already understand their place in it.

We, however, will imagine ourselves boarding Vito Andolini’s ship and taking her return journey back to the gulf of Naples (from where she likely sailed). And our journey will not only be a journey through back through space. It will also be a journey back through time. We will not arrive in the Naples of her fading twentieth century glory – the capital of a once enduring kingdom that had borne her name for centuries. For this city’s history is long and stretches back to the edges of humanity’s written story.

We will arrive long before: when no city yet existed here. Villages mark the shoreline – visible from a distance from the smoke rising from them. Much of the shore is forested. Though we also see tended fields on this fertile Campanian plain. Mt Vesuvius will be a familiar landmark rising in the distance. It is due to erupt. But it not the famous eruption that entombed the city of Pompeii. Rather it is an eruption that happened long before in the depths of forgotten time.

[1] Fred Gardaphé, Invisible People: Shadows and Light in Italian American Culture in Connell, William J. (2010-12-19T23:58:59). Anti-Italianism: Essays on a Prejudice (Italian and Italian American Studies)

[2] From Preface to reprinting of The Fortunate Pilgrim